Most investment professionals, and most financial journalists, have a problem with the idea of randomness. They see patterns, even when there aren’t any, and they like to use those patterns to make predictions about the future — for example, which asset classes are about to rise or fall in value, which countries are due a winning streak, and which funds are going to outperform the market in the years ahead.

The truth is that movements in the financial markets are essentially random. All known information is incorporated into prices. It’s new information that causes prices to rise and fall, and, by definition, new information is unknowable — unless, of course, you’re an insider, in which case you’re breaking the law by trying to gain financially from it.

That’s why, to use the analogy Louis Bachelier chose in his famous 1900 thesis, The Theory of Speculation, future market movements are no more predictable than the steps of a drunkard.

But just because the markets are random, that doesn’t mean they’re lawless, or that there isn’t a pattern to market returns. “Le marché,” wrote Bachelier, “à son insu, obéit à une loi qui le domine: la loi de la probabilité.” (“The market, without knowing it, obeys a law that dominates it: the law of probability.”)

So, although it’s almost impossible to predict the price movement of a given stock on a given day, price movements over time fall into a stable frequency pattern, in the same way that repeated tosses of a coin fall into a 50-50 pattern of heads and tails.

Investors, then, need to think in terms of probabilities, average returns and the extent to which returns deviate from the average.

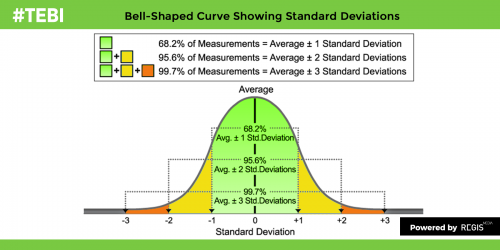

If you look at returns over the long term they form a classic bell curve, otherwise known as a normal distribution, or Gaussian distribution. The curve represents a set of outcomes; let’s say the outcomes are the monthly returns of an investment.

In the middle of the graph is the average return, and, clearly, the vast majority of outcomes are concentrated around that average. This is the result of what statisticians refer to as reversion to the mean. The green area accounts for approximately 68% of all the outcomes in a period. The green and yellow shaded areas combined account for 95.6% of outcomes, and, when added together, the green, yellow and orange areas account for 99.7% of outcomes.

It would be great, of course, if we could find a way of shifting the bell curve to the right. The investing industry is brimming with people who claim to be able to do it, either through stock selection or market timing. The overwhelming evidence is that no one in modern times, with the possible exception of Warren Buffett, has been able to do it on a cost- and risk- adjusted basis with any degree of consistency; and even Buffett has struggled to beat the market return in recent years.

Investors, then, should focus not on trying to beat the market, but on capturing market returns in the most efficient way.

So, is it possible to shift the distribution curve to the right? Can investors do anything to produce higher than average net returns over the long term? The good news is that the answer to both questions is yes. There are, in fact, three reliable ways of doing it.

The first way is to tilt your portfolio towards risk factors that have been shown, over time, to outperform the broader market; small-cap stocks, for example, have beaten, large-caps, and value stocks have outperformed growth stocks. But, remember, if you do that you have to accept a greater degree of volatility, and there is no guarantee that these risk premiums will persist in the future.

A second and more reliable way to outperform the average investor is very simple — and that’s to reduce your costs. Peter Westaway, Chief Economist for Vanguard Europe, sums it up neatly in a new article for FT Adviser:

“The impact of costs shifts the return distribution to the left. A high-cost investment moves the return curve much farther to the left than a low-cost investment, making outperformance compared to both the market and the low-cost investment much less likely. In other words, after accounting for costs, the total performance of investors is less than zero sum.

“As costs increase, the performance deficit becomes larger, and the likelihood of underperformance increases until significant underperformance becomes as likely, or more likely, than even minor outperformance.”

The third and final way to shift the distribution curve to the right is to manage your behaviour. Don’t give in to your emotions and don’t be tempted to buy or sell just because everyone else is. Apart from occasionally rebalancing your portfolio to restore the original asset allocation, you should ignore the noise and leave things exactly as they are.

In fairness, that’s just about everything an investor needs to know about normal distribution. However, the mathematics behind it is fascinating, and it impacts on so many areas of life, not just investing.

If you’d like to learn more about this subject, you ought to watch a new three-part video series that my colleagues and I have produced for Index Fund Advisors in California about the Galton Board. It was the Galton Board, designed by the Victorian statistician Sir Francis Galton, which provided the first practical illustration of normal distribution in action. Galton’s specific interest was in human heredity and how traits such as height are passed down between generations.

We posted the first video in the series, on binomial distribution, last week. The second looks in more detail at reversion to the mean:

If you have a particular interest in financial mathematics, or in mathematical history, you might also like to watch this video series we produced for Index Fund Advisors last year. It’s a three-part series looking at Sir Francis Galton’s life at work, and explaining some important lessons that Galton can teach investors today:

Sir Francis Galton: Whenever you can, count (1/3)